Chile: From Democratic Transition to Social Outbreak

- The different generations of young people, from the dictatorship to the present day, have built with enormous sacrifices the social changes towards the path of “opening the great avenues,” as foretold Salvador Allende in his last speech at the Moneda presidential palace in September 11, 1973.

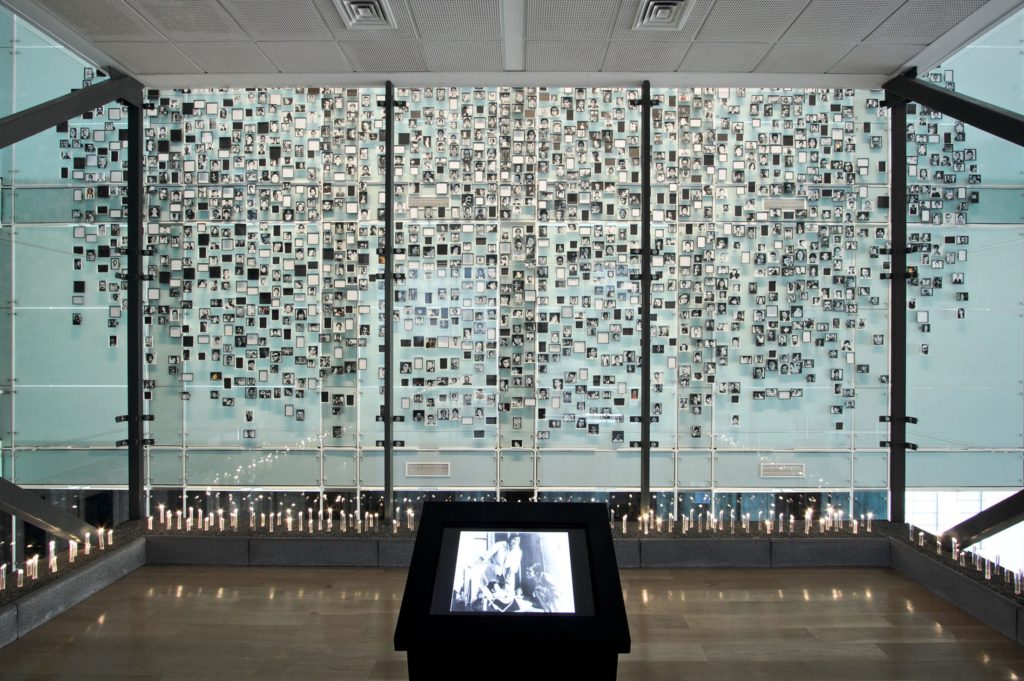

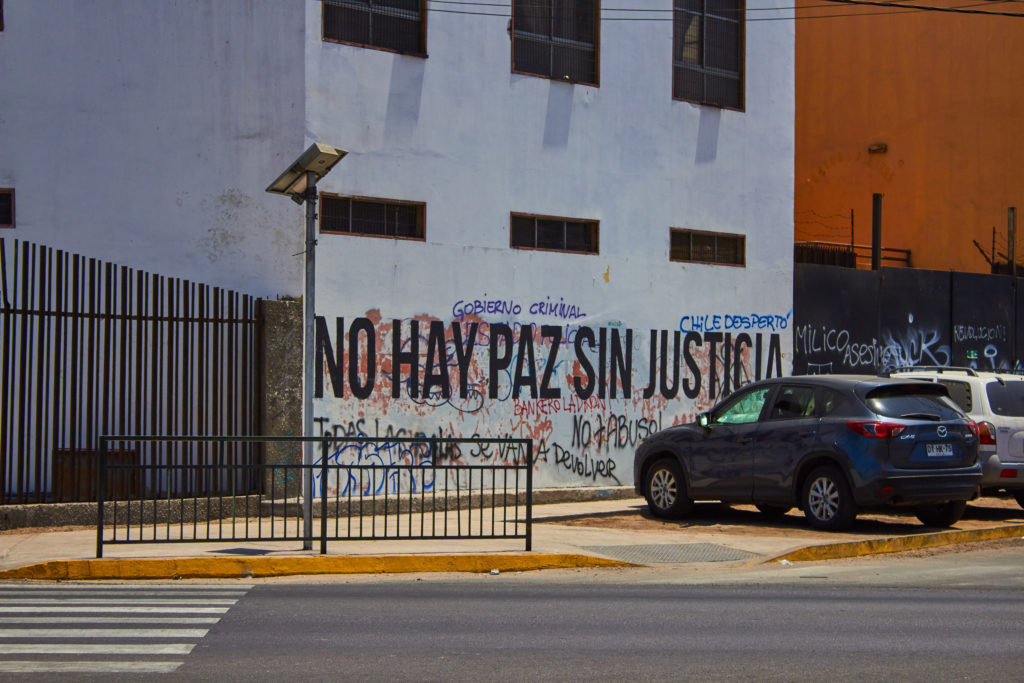

- The motto “Chile woke up” is the memory and collective conscience of a society weary of an unjust model. It is the story of thousands of fellow citizens who were victims of state terrorism. It is the account of the thousands of citizens who had to endure the years of silence, repression and inequality. It is the memoir of my father and mother who fled to Costa Rica to form a new life from scratch. It is also the reality of us, the sons and daughters of exiles.

From 1997 to 2002, I lived in Chile during a special time, when several political exiles started to return in the 90s after the dictatorship that lasted for 17 years. It felt like an awakening moment by which I recognized an important part of my history that had been somewhat blurred. I learned more about my mother and father‘s political activism in the late 60s and early 70s.

I was a 15 year-old high school teenager having switched from the Costa Rican to the Chilean French Lyceum. I happened to unexpectedly share the classroom with other children of exiles, with whom I lived important events and got to know their own personal stories, having built with every single one of them strong friendship ties. Over the years, I discovered new friends, some with tragic experiences. Disappearances, torture and murders are shocking and traumatic episodes that no family should ever suffer. The cruelty perpetrated in Chile is something that remains hard to understand.

A changing and afraid society

When I arrived in the mid-1997, it was the second government of the coalition called “Concertación de Partidos por la Democracia.” The Christian Democratic party was elected for two consecutive governments – from 90 to 94 with Patricio Aylwin and from 94 to 2000 with Eduardo Frei. This period was known as “Transition,” which was the term used to define the process of adjustment of Chilean society to the new democracy.

The dictator was still present in Chile’s everyday life holding the position of Commander in Chief of the Military until March 1998, when he retired and took a seat as senator for life that was safeguarded by the 1980’s Constitution. There was a great fear in Chilean society. Dreading reprisals, citizens and political representatives did not seek to promote structural changes to the system due to the threats of re-establishing an authoritarian regime.

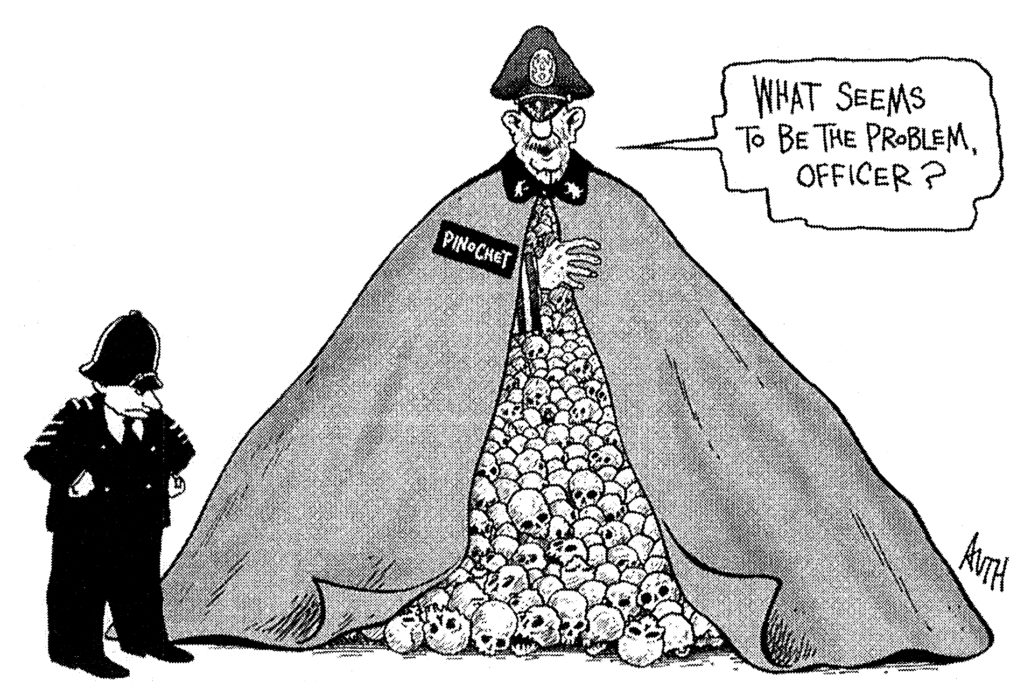

Suddenly, in October ’98, an unpredicted event would occur. Something that many thought would never be possible. Augusto Pinochet had been arrested at a clinic in London, England. The Spanish judges Baltasar Garzón and Manuel Garcia Castellon had in hands an international warrant. It was an Interpol Red Notice against Pinochet requesting his extradition from the United Kingdom to Spain, to try him for crimes against humanity within the ambit of the Operation Condor. This event would mark international jurisprudence.

Until that moment, all signs had indicated that the dictator would never lose his power and would enjoy impunity and freely live the rest of his life in peace. This whole scenario faded with his arrest abroad. For the families of detained-disappeared and all victims of state terrorism, it was finally some justice for the crimes committed by the tyrant.

I myself remember the occasion that I gathered with friends at the Plaza Italia (today’s renamed Plaza Dignidad) to celebrate Pinochet’s arrest. My memory still recalls the huge number of people there and their happiness. The rally would finish with a violent repression by the police. Over the years, I came to realize that violence had always been there, over and over again. This was one of my first demonstrations and I could immediately notice that the attack had been sparked by the police with their infamous “guanaco” or water-launch truck. Then, they would shoot tear gas dispersing the crowd, and, at the end of the day, a few protesters and the policemen would be left in a pitched fight until dawn, leaving behind a trail of destruction and damages in the square and surrounding areas.

As of today, with the social outbreak of recent months in Chile, this “déjà vu” of police bellicosity has ended up spiraling out of control, causing human rights violations almost at the same level as back in the dictatorship years. Amnesty International (AI), Human Rights Watch (HRW), United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and the National Institute of Human Rights (INDH) have all issued full reports documenting the abuses of the authorities.

During my high school and university years, it was clear to me that the neoliberal economic system been implanted in Chile produced a gap of deep social segregation and inequality. This was easy to visualize having my native Costa Rica as a reference, where a welfare state has been in place for many years. A similar experience happened with other children of exiles, who had lived in different political systems with higher levels of equality and social justice. I remember that this comparison used to be a matter of conversation between my friends and I. By then, we were pretty certain that the country was a time bomb and could explode in a not too distant future if a change was not done.

In 2000, when I started the university, there were the hard-fought elections between the socialist, Ricardo Lagos, and the right-wing of the Independent Democratic Union, Joaquín Lavín. After a tense presidential campaign in which a large part of the young people did not participate, Lagos prevailed by a minimum margin. He inherited the “Pinochet affair,” who had been under arrest in London for a year and a half. The government managed to bring him back by committing that the Chilean justice would prosecute him. Having lasted eight years, this imbroglio did not end in his condemnation.

Nonetheless, the dictator would suffer the betrayals of some of his close politicians and the entire burden of the judicial process until his death, on December 10, 2006, ironically, International Human Rights Day. His passing happened during the beginnings of the second socialist government led for the first time in Chilean history by a woman, Michelle Bachelet.

A complex new world order

In the international context, the attacks of September 11, 2001, in the United States, the same day as the coup d’état in Chile, 28 years earlier, marked a worsening of international conflicts with effects in all countries. George W. Bush started the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and imposed a wild free market economy.

Lagos strongly opposed the military aggression in Iraq, and many Latin American governments will move in those years to the left. At the end of the Bush’s tenure in 2008, an acute global economic crisis broke out, resulting in the election for the first time in US history of an African American: Barack Obama.

In the first months of 2002, I returned to Costa Rica with my family. It was a complicated return, since Chile had changed me forever. Shortly after, I would suffer the painful loss of my mother in 2003. Despite this, I would firmly pursue my journalism studies and would graduate in 2005. Before graduating, I had already experience in building websites (a skill that I learned on my own) and I created a political website for a group of Costa Rican intellectuals, who viewed with concern the world panorama and the future at that moment. I took this opportunity to publish my first independent journalistic pieces.

Meanwhile, in Chile, the neoliberal elite praised its own system with the force of the private media. Internationally, it was seen as a “successful model.” Nevertheless, the first student marches dated from 2006 proved this prosperity was cracking and did not include the overall society. Named “The Penguin Revolution” (due to the student’s uniforms in Chile), the rallies claimed for a free and quality education. This first wave of demonstrations, gradually gained strength over the years and added other discontented groups and movements.

An incomplete transition to democracy

The “Concertación,” the political coalition that had promised to bring joy and that in fact achieved certain important reforms, was unwilling to deepen the changes to the exclusionary economic model. With such a complex reality in those early years, Pinochet’s arrest could have marked a golden opportunity, even, for changing the dictatorship’s Constitution. The coalition and its leaders worn away, without renewing their political figures and ideas, eventually causing strong divisions and fragmentation that allowed to the right to access power on two occasions.

In the 2010 general election, for the first time since the return to democracy, the winner was the center-right candidate of the National Renewal party, Sebastián Piñera. Both during his first term and nowadays, he did not possess the political wisdom to perform a modern political project in the style of the European center-right. Due to commitments with sectarian political figures, especially in its second government, the Chilean right has brought back the tragedy of human rights violations and crimes of the dictatorship, making its future democratic projection very difficult.

On the other hand, the slow and late reform of the electoral system, which only established automatic voting in 2012 and ended the binomial in 2018, exposed the fragile democratic culture. In the last electoral process that Piñera won, there was more than 50% abstention. Having a large part of the population excluded from the electoral system for years, the outcome was unsurprising.

In addition to this, the well-known cases of corruption that have involved the entire political and business spectrum in the last 10 to 15 years generated distrust and discredit among society. The forge of an economic system that allowed large companies to control essential resources and services added to a historical accumulation of debts to citizens, became the catalysts for the strong Chilean social outbreak of October 14, 2019.

Witnessing the transformation

I visited the country before and after the social outbreak: in January 2017 and later in December 2019. This provided me a clear picture of the situation in Chile. The idea of my first trip was to settle there. This did not happen and I returned to Costa Rica. I could already see that the social situation had deteriorated even more. The high cost of living coupled with the skyrocketing rise in the house rents left the population with an ever shrunk purchasing power.

Likewise, I realized that there was an increasing job instability and low wages, as well as a regulatory framework that remained weak to protect workers. These factors, in addition to the high crime rates that the country was experiencing, revealed to me that Chile was at the brink of the explosion of the time bomb that we had envisaged years before.

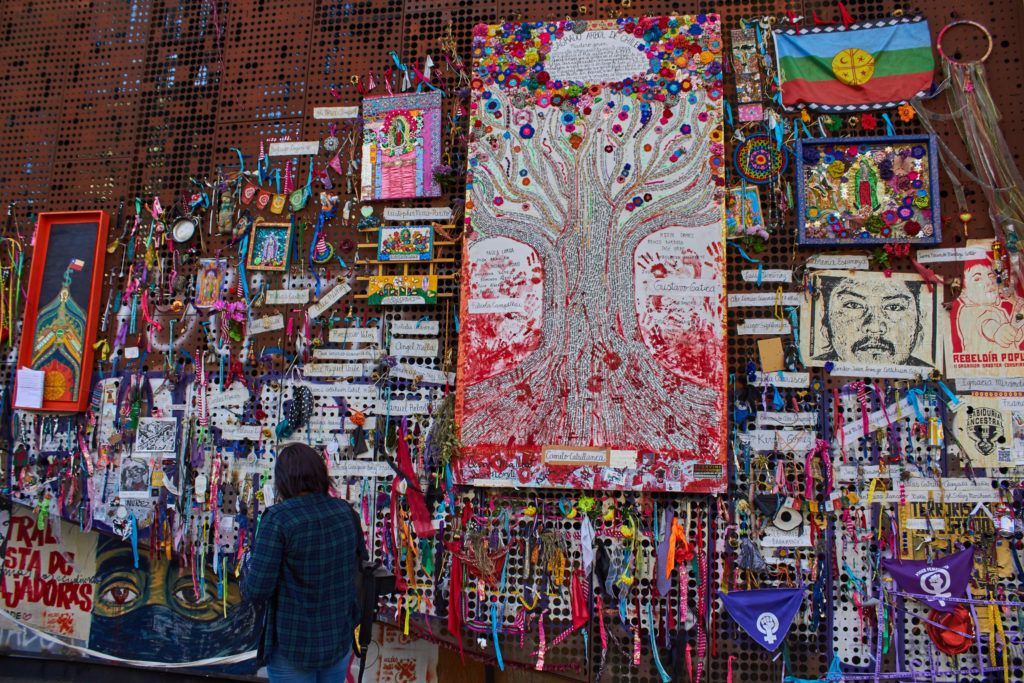

In December last year, I returned with my wife, who is also a journalist. We witnessed the energy and vibrant strength that was emanating from the citizen movement. The society was effervescent and demonstrated with countless artistic and cultural expressions all over the country. Walking down the streets of Santiago, we appreciated the magnitude of the protests and their demands. We could feel a great consensus among people that there ought to be a change in the “status quo”.

Chile is experiencing a revolution that has had an impact beyond its borders. The originality and strength of the feminist movement that crossed boundaries has been admirable. Many Chilean friends living abroad, were just as curious as us to travel and bear witness to what was happening in the country. It was heart-warming to meet several of them in the capital Santiago.

We spent somedays in the harbor town of Valparaíso, another epicenter of strong demonstrations and considerable police repression. We saw the struggle on its hills. A large graffiti that could be seen from far away stamped in capital letters “NEW CONSTITUTION,” which is the main demand of the people. Inside a community garden, a discreet message said “sowing revolution, cultivating freedom.” The streets of all Chile are covered with the claims of the outraged citizens.

In our summer journey, we headed to the remote northern town of Chile, Iquique, where the desert meets the Pacific ocean, in the Tarapacá region. Over there we saw again the informal street vendors like in Santiago and Valparaíso. They were profiting from the sales of attractive souvenirs that recalled the revolution in progress. We also walked by painted walls with graffiti and artistic pieces screaming for their rights with indignation. The regional Tarapacá government building was closed and had damages in its walls and windows. The rage of the citizens was clear against everything that represented or reminded the political and governmental authorities.

The Piñera government has had a totally erroneous and disastrous handling of the crisis. The global pandemic of the new coronavirus that had recently forced countries to impose lockdown measures is likely to give the president a break, a pause. It would be a mistake though to think that after the pandemic everything could continue the same. After months of social resistance in which people have had to endure brutal repression and that national media proved unable to report truthfully and impartially, the determination and willpower of the citizen movement for change is unstoppable.

2. Graffiti: “There is no peace without justice.”

3. A building painted with the word “RAGE!” in capitals.

4. A young boy named José Vergara who suffered from schizophrenia disappeared by the police on September 13, 2015.